A dancer’s pay in the U.S. is unpredictable. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly pay for dancers and choreographers in 2023 was $24.95. But that number belies a wide range of experiences, with pay fluctuating depending on location, career level, and freelance status, among many other variables.

All too often, the pay a dancer receives seems less than what their work is worth. As a result, unions and protests have grown in the industry. Dance artists are getting increasingly comfortable demanding more and speaking up about their work conditions.

To help paint a picture of the current financial landscape in the industry, four dancers got candid about their typical earnings—and the financial needs and concerns that shape their careers.

Nicole Pedraza

Contemporary dance artist and choreographer, Miami, FL

Pedraza in Untitled or Monument: a visual metaphor of spontaneous disintegration in Plaster of Paris. Photo by Simon Soong, Courtesy Pedraza.

“I get very nervous about trying to make ends meet,” Pedraza says. “What’s holding me back is definitely the lack of consistency in dance work in my city.”

Pedraza has four main forms of income. She has a flexible, full-time arts administration position that pays $19.31 an hour. She is part of two dance collectives; one pays $30 per hour for rehearsals, while the other pays per performance. The frequency of work for both depends on the annual performance schedules. She books sporadic freelance performances and choreographic gigs. And she teaches several times a week at her childhood dance studio, for which she earned $35 per hour last year. (Pedraza requests at least $50 per hour when teaching elsewhere.)

She has money saved from college financial aid and scholarship stipends after graduating in 2021, giving her a layer of comfort. But keeping up with her schedule gets tiring.

Pedraza’s earnings primarily go towards bills and helping her mother financially. Her car bills are her top priority. She got a new car this year because her old one kept breaking down when she traveled between 50 minutes and an hour and 15 minutes for rehearsals and performances.

Before getting her full-time job, she contemplated solely working as a dance artist. She calculated the pay for dancers in Miami and the number of opportunities available and concluded that it did not offer a livable wage.

“This year, I was sitting back and analyzing and thinking like, Oh, I’m very proud of myself for continuing to pursue dance and my dance career, my choreographic career,” she says. “Because it very much felt impossible financially, especially when no one talks about it.”

Jay Carlon

Freelance dance artist, Los Angeles, CA

Carlon’s work focuses on community engagement through dance and multidisciplinary performance. His earnings depend on the nature of his dance practice—whether it involves freelance choreography commissions or teaching movement and somatic-based workshops. Most of his income goes towards paying back credit card bills for professional-development expenses.

Carlon was part of the first class of FARconnector’s Designed Executive Fellowship Team, an arts administration fellowship that fostered three-year partnerships between artists and arts workers. For 2023, the joint efforts of Carlon and his producer/DEFT fellow Brian Sea resulted in national, state, and local Los Angeles City grants, through which they paid themselves each a base income of $1,000 per month.

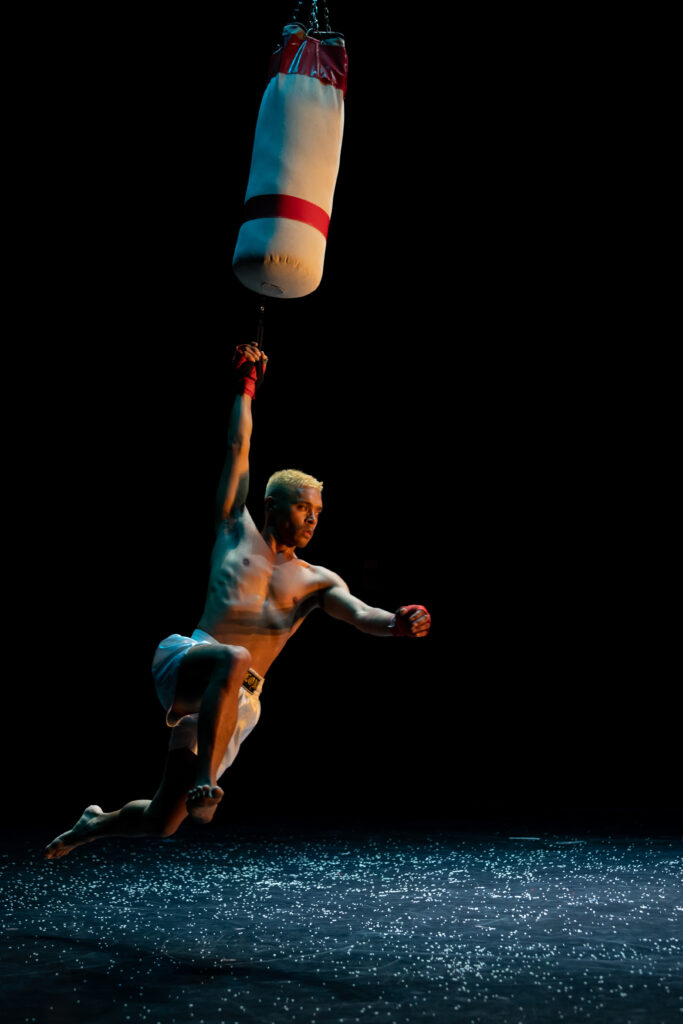

Carlon in WAKE. Photo by Angel Origgi, Courtesy Carlon.

Carlon in WAKE. Photo by Angel Origgi, Courtesy Carlon.

Recently, Carlon performed in Joan Jonas’ Mirror Piece I & II at the Getty in Los Angeles, which faced backlash after it was revealed that the dancers only received a $1,000 flat rate for eight days of work that included six-hour rehearsals and two performances. Dancers in a previous performance at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City had received $150 to $200 per day for rehearsals and $750 to $1,500 per day for performances, according to the performer call.

Carlon, who is active in labor rights efforts, initially brought the discrepancy up to the other dancers in an email, explaining that from an institution of this size and wealth he’d expect $40 to $50 per hour of rehearsal and $400 to $1,000 per performance. “I am very grateful for this performance opportunity, and frankly I think we should get paid more,” he wrote in the email, “especially since the Getty (Trust) is the world’s wealthiest arts institution.”

Carlon’s biggest challenges involve the scarcity of arts funding. He said he spends more time writing unguaranteed grants than creating work each year. He’s received seven rejection letters from grants so far this year.

“The current system is way too competitive and weird, so I’m searching for different ways of operating,” he says.

Nat Wilson

Contemporary dance artist, New York, NY

Wilson in Through the Fracture of Light. Photo by Alice Chacon, Courtesy Wilson.

Wilson in Through the Fracture of Light. Photo by Alice Chacon, Courtesy Wilson.

Wilson has a small financial cushion thanks to severance pay from a previous full-time job with Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company in Israel, which they left in October 2019. But after moving to New York City in January 2020, the pandemic arrived, and they witnessed their “whole career dry up in a weekend,” Wilson says.

They started online school at Washtenaw Community College to pursue an associate degree in human services. While in school, they received $5,000 every six months from an unused tuition fund their parents had—a privilege Wilson acknowledges.

Last December, they completed their degree, and this year, they transitioned to dancing full-time. They earn about $20 per hour for rehearsals and usually $100 per performance.

They also became a certified teacher in FoCo Technique, created by Yue Yin, and teach FoCo classes at 92NY, where each class pays $150. Other classes they teach typically pay per student.

Smaller forms of income include driving for a delivery app, which pays about $200 per month.

In total, they earn about $500 a week—enough to cover bills and see shows or eat out once in a while, but not enough to contribute to savings. “I’ve been living in this kind of lifestyle for so long that I have trouble conceiving what it would be like if I made more money,” they say.

Alexandra Light

Principal dancer, Texas Ballet Theater, Fort Worth, TX

Though Light’s contract prohibits her from sharing her annual salary, as a principal she earns more than most dancers at TBT. She ruefully quotes a saying: “The highest-paid dancer doesn’t even make half of what the lowest-paid symphony member does.” Although that’s an exaggeration, the pay disparity is real.

“We train so hard, and our training is expensive,” Light says. “I’m not saying we need to get paid like a neurosurgeon, but we need to at least make a living wage.”

Light is married, and some years her husband has earned more than she has. His highest annual salary, for work in art sales and retail management, was $50,000.

Light in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar, Courtesy Texas Ballet Theater.

Light in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar, Courtesy Texas Ballet Theater.

But currently, the couple is in a transitional period. Light’s husband is in school, studying art history. Light is retiring after this season to focus on her choreography, a part of her career that she’s been able to foster over the past few years.

As she prepares for that pivot, Light is mostly concerned about the unpredictability of freelance pay. In the past two years, her commission rates have ranged from $500 to $3,000 per piece.

“Working on a variety of different types of projects with a mix of budget sizes has been very rewarding, so it is all about trying to figure out what is the best fit,” she says. “You need to feed your bank account but also feed your artistry—that’s been a big takeaway for me.”

One of Light’s professional goals is to help eliminate the pressure on dancers to work for free. “I will work as hard as I can to make sure that the funding is secured before any project happens,” she says.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings