Panya Mingthaisong/iStock via Getty Images

In 2022, we discussed the market’s deviations from long-term growth trends. That discussion centered on Jeremy Grantham’s commentary about market bubbles. To wit:

“All 2-sigma equity bubbles in developed countries have broken back to trend. But before they did, a handful went on to become superbubbles of 3-sigma or greater: in the U.S. in 1929 and 2000 and in Japan in 1989. There were also superbubbles in housing in the U.S. in 2006 and Japan in 1989. All five of these superbubbles corrected all the way back to trend with much greater and longer pain than average.

Today in the U.S. we are in the fourth superbubble of the last hundred years.”

Are we currently in a market bubble? Maybe. Honestly, I have no idea. The problem is that market bubbles are only evident and acknowledged after they pop. This is because, during the inflation phase of the market bubble, investors rationalize why “this time is different.”

As we noted then, there are three components of market bubbles:

Price Valuations Investor Psychology

When investors bid up asset prices that exceed underlying earnings growth rates, market bubbles were previously present. Since economic activity generates revenues and earnings, valuations can not indefinitely exceed the underlying fundamental realities.

Interestingly, the correction in 2022 started the reversion process of that deviation. However, investor speculation has since pushed that deviation near its previous peak.

As is always the case, valuations are a function of price and earnings; therefore, deviations in price from the long-term exponential growth trend have marked prior peaks. Unsurprisingly, when price momentum increases rapidly, investors rationalize why overpaying for earnings is justified this time. Unfortunately, as shown, such has rarely worked out well.

As the chart shows, and the definition of a market bubble states, “assets typically trade at a price that significantly exceeds the asset’s intrinsic value. Instead, the price does not align with the fundamentals of the asset.”

Crucially, as previously discussed, excess valuations and price deviations from long-term norms are solely a function of investor psychology.

“Valuation metrics are just that – a measure of current valuation. More importantly, when valuation metrics are excessive, it is a better measure of ‘investor psychology’ and the manifestation of the ‘greater fool theory.’ As shown, there is a high correlation between our composite consumer confidence index and trailing 1-year S&P 500 valuations.”

What valuations do provide is a reasonable estimate of long-term investment returns. It is logical that if you overpay for a stream of future cash flows today, your future return will be low.

So, why are we rehashing this topic?

An Optimistic Bunch

While sufficient data suggests that economic growth rates are weakening, investors are again chasing assets with near reckless abandon. For example, investor allocations to equities are rising sharply as chasing asset market returns displaces logic and underlying fundamentals.

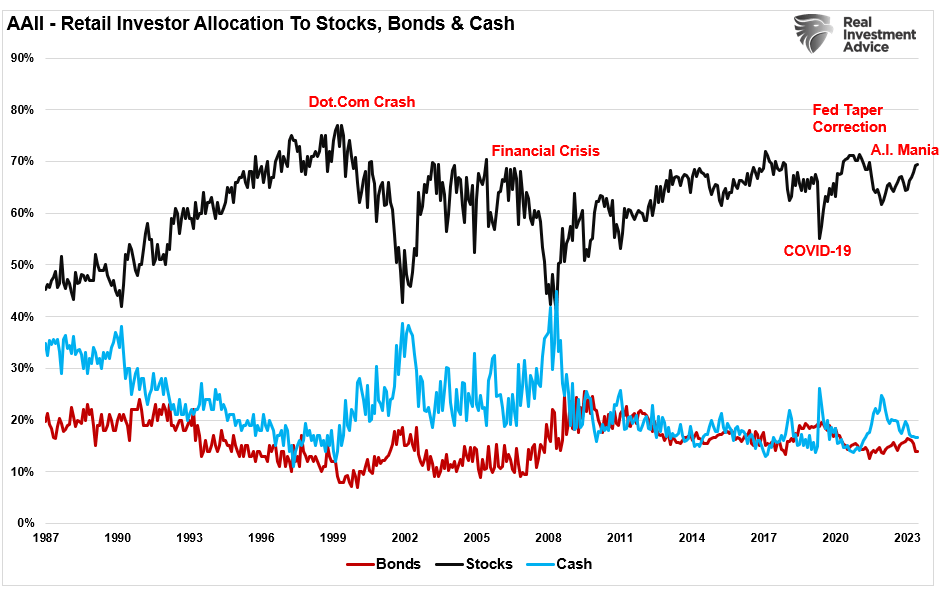

The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) allocation measures suggest the same, with investors increasing exposure to equities and reducing cash.

Furthermore, extremely low levels of volatility suggest a high level of complacency among investors. Historically, low levels of market volatility tend to reverse suddenly.

Suppose we create a composite index of investor sentiment and volatility (when one is high, the other is low). In that case, current levels align with short- to intermediate-term market peaks and corrections.

Does this mean the market is about to crash? No. However, as Howard Marks previously noted:

“We can infer psychology from investor behavior. That allows us to understand how risky the market is, even though the direction in which it will head can never be known for certain. By understanding what’s going on, we can infer the ‘temperature’ of the market.

We must remember to buy more when attitudes toward the market are cool and less when heated. For example, the ability to do inherently unsafe deals in quantity suggests a dearth of skepticism among investors. Likewise, when every new fund is oversubscribed, you know there’s eagerness.”

Currently, there is little denying the more excessive bullish sentiment that abounds. Investors are willing to take on risk, overpay for underlying valuations, and rationalize their actions. Historically, these actions have been the precedents of markets where expectations exceed underlying fundamental realities.

However, while that may indeed be the case, we must never forget the famous words from John Maynard Keynes:

“The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Managing Risk And Reward

Whether you agree that current market deviations are important is mostly irrelevant. Every investor approaches investing differently. We spend much time researching current market environments to reduce the risk of catastrophic losses. Does that guarantee we will be successful in that endeavor? No. However, understanding the risks we are undertaking helps us quantify capital destruction in case something goes wrong.

Managing risk is far more crucial if you are nearing or have entered retirement. The reason is that your investment horizon is shorter than that of those much younger. Therefore, you are less able to recover from short-term market repricings.

There are some simple steps you can take to prepare yourself.

Avoid the “herd mentality” of paying increasingly higher prices without sound reasoning. Do your research and avoid “confirmation bias.” Develop a sound long-term investment strategy that includes “risk management” protocols. Diversify your portfolio allocation model to include “safer assets.” Control your “greed” and resist the temptation to “get rich quick” in speculative investments. Resist getting caught up in “what could have been” or “anchoring” to a past value. Such leads to emotional mistakes. Realize that price inflation does not last forever. The larger the deviation from the mean, the greater the eventual reversion. Invest accordingly.

The increase in speculative risks and excess leverage leaves the market vulnerable to a sizable correction. Unfortunately, the only missing ingredient is the catalyst that brings “fear” into an overly complacent marketplace.

Currently, investors believe “this time is different.”

“This time” is different only because the variables are different. The variables always are, but outcomes are always the same.

When the eventual correction comes, the media will tell you, “No one could have seen it coming.”

Of course, hindsight isn’t very useful in protecting your capital.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings